Why teachers like me...

What's a "teacher like me"? That would be a young third-year teacher with a masters' in mathematics, teaching mixed level courses at a small city school offering only the challenging IB programme to kids who generally are from low socio-economic groups in Stockholm, Sweden. I love my work, LOVE it, and spend way too much time striving to develop effective teaching based on sound research principles.

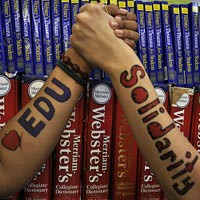

What's a "teacher like me"? That would be a young third-year teacher with a masters' in mathematics, teaching mixed level courses at a small city school offering only the challenging IB programme to kids who generally are from low socio-economic groups in Stockholm, Sweden. I love my work, LOVE it, and spend way too much time striving to develop effective teaching based on sound research principles....support unions.

I'm a member of one of Sweden's largest teacher unions, Lärarförbundet. Financially, and in terms of job security, there is no point in this membership - I have tenure and unions do not influence salary. Instead, the reason I support unions is because it is important to offer organized resistance to changes initiated, and sometimes even determined, by the many levels of school leaders.

Examples of such changes are increases in teaching hours as well as in administration and class sizes, all of which means decreases in the time we have to do a good job.

I am always astounded by how little non-teachers seem to be aware of how much work it takes to plan a good lesson. I have friends who teach at in universities, as teacher assistants; they have 4 hours for each hour of "lesson" (more like a seminar, really). Usually high school teachers have about one hour per hour of teaching, and this is supposed to cover preparing the lesson as well as marking any work collected from the students during the lesson. Teachers at lower levels typically have even less.

At the same time, teachers are blamed for not being good enough at explaining, engaging, motivating, fostering, caring, investigating, communicating with parents, cooperating with other teachers, organizing events, devising individual development plans, following new research, taking part in professional development, and documenting results. The expectations are wildly unrealistic given the constraints; as a result teachers get sick, get cynical, get divorced, or leave for something different. Meanwhile, what is happening with the students of these sick, cynical, sad and absent teachers?

These kinds of changes are happening in Sweden, where currently there is no limit on the number of hours a teacher can be ordered to teach. Some twenty years ago the average was about 14 hours (60 minutes) per week - I currently teach 18.5 hours and in other schools teachers teach up to 30 hours per week. We also don't have any restrictions on how many other tasks a teacher can be assigned, and there is no lower limit for how much time for planning and marking a teacher is entitled to. The only limit is when a teacher is assigned so much work that he or she becomes overworked and sick, and even then measures taken are to temporarily repair the damage, instead of permanently fix the situation.

Does anyone think this is reasonable? Does anyone think that teachers who are talented or lucky enough to have other options, will want to stay at a job such as this one?

This is the reason I support unions: by myself I can achieve little to improve even my own situation, and much less anyone else's. Together we can resist and maybe even reverse some of the developments which over the last couple of decades have undermined the high quality in education that we as teachers, as students, and as a community, are striving to achieve.